- Intro to Music Theory

- Lesson 1: Naming The Musical Notes

- Lesson 2: Sharps, Flats, and Naturals

- Lesson 3: The Major Scale

- Lesson 4: Major Chords

- Lesson 5: Musical Intervals

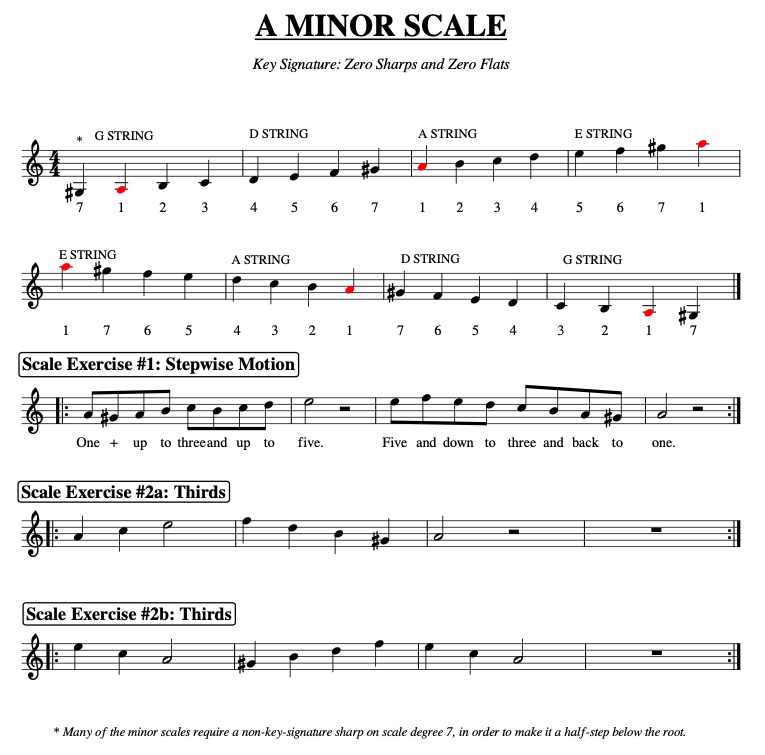

- Lesson 6: The Minor Scale

Sharps, Flats, and Naturals – In the previous lesson, we learned that the natural notes have names corresponding to the first seven letters of the alphabet. We saw where to find them on a few musical instruments. We learned that the notes are not all located the same distance apart. For example, on the mandolin fretboard below you can see that the B and C notes, and the E and F notes are closer together than the other notes.

The distances between musical notes are called intervals. Intervals between notes are all important in understanding music. You may not know this, but when you played the natural notes in order, in the last lesson, from the lower A note to the higher A note, you were playing a musical scale: The A minor scale. Why is that the A minor scale? Because of the intervals between the notes! It creates a musical pattern with a sad, haunting sound that we associate with a minor key. In this lesson, I’ll discuss intervals, but in the next lesson we’ll discuss musical scales beginning with the major scale.

It’s So Very Simple

The good news is that there are only seven natural note names in Western music – and there are only 12 actual notes altogether! You’ve noticed the black keys on the piano, and the unused frets between some of the notes we looked at in previous lessons. The black keys, and empty frets between natural notes, can seem a bit scary to some people, but they’re just a few more notes that make up the twelve notes of Western music. Learning about these notes is pretty easy. Understanding notes and intervals is not really difficult. The complexity in music comes because there are a nearly infinite number of ways to combine note patterns and rhythms. What we’re learning right now is similar to learning about bricks. Not very complicated. But with simple bricks and some imagination, you can build an infinite number of architectural variations. For now, think simple, and let’s understand intervals a little.

Steps, Half-steps and Octaves

The basic building block intervals for musical notes are whole steps, half steps, and octaves. A whole step is also known as a tone and a half-step is also known as a semi-tone. I am writing as an American, but the terms “tone” and “semi-tone” are more common in Great Britain and Europe.

Look at the piano keyboard:

If you begin playing on the low A key as in the picture above, and you play every black key and white key in order until you get to the next A note, you will have played all 12 notes of Western music + ending on an A note of higher pitch. The second A note is one octave apart from the first A note.

The twelve notes of Western music are as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

A – A#/Bb – B – C – C#/Db – D – D#/Eb – E – F – F#/Gb – G – G#/Ab

(Notes in black are natural notes we’ve seen before; the others have two names and correspond to the black keys on a piano keyboard)

But what is a half step? Each “next key” on the piano keyboard, including black & white, is one half step. From the bottom A white key to the next black key (A#) is a half step; from the black key (A#) to the white key (B) is a half step; from the white key (B) to the white key (C) is a half step; and from the white key (C) to the black key (C#) is a half step.

And what is a whole step? Well we know that two halves equal a whole, so a whole step between notes means two half steps between notes. Since each next piano key, white and black, is a half step apart, then skipping one key between two notes means that those notes are a whole step apart. Exercise: Read the following, and after reading each statement, refer to the piano keyboard above.

Notes A and B are a whole step apart; they skip one key, the black A# key.

Notes B and C# are a whole step apart; they skip one key, the white C key.

Notes C and D are a whole step apart; they skip one key, the black C# key.

Notes C# and D# are a whole step apart; they skip one key, the white D key.

A# is a half step up from A, it is the next adjacent key.

B is a half step up from A#, it is the next adjacent key.

C is a half step up from B, it is the next adjacent key.

The relationship between notes (half steps, whole steps, octaves) that we discussed while considering a piano keyboard is also reflected on the guitar and mandolin fretboards. Each next fret is a half step; therefore, skipping one fret between notes is a whole step. Read the above exercise again, substituting the word “fret” for the word “key” where appropriate. Refer to the images below after reading each statement and you’ll find the same patterns:

Examples:

Notes A and B are a whole step apart; they skip one fret, the A# fret.

Notes B and C# are a whole step apart; they skip one fret, the C fret.

Are They Sharps or Flats?

We learned in previous lessons that the white keys on a piano are called natural notes. These notes are named A, B, C, D, E, F and G. These notes are of unequal distance, in that there is a half step between B and C, and there is a half step between E and F, and all other natural notes are a whole step apart. That’s why all the white keys of a piano have black keys in between except the keys for B and C, and the keys for E and F. Look at the piano diagrams below:

Moving up the keyboard from the lowest A note shown —>

Moving down the keyboard from the highest A note shown <—

Lowering the A note one half step makes the A note flat (Ab,second image above), while raising the G note one half step makes the G note sharp (G#, first image above). G# and Ab are the same black key on the piano keyboard. Each note represented by a black key on the piano has two names, a sharp name and a flat name. The name used depends on whether the nearest natural note has been raised a half step or lowered a half step. There are good musical reasons why we have to consider whether an A note is being flatted, or a G note is being made sharp. Don’t worry about the “why” for now, we’ll see the reasons soon enough when we study scales and chords. The intervals (distances between notes) are everything! For now, learn these two important truths: Lowering any note by a half step makes it flat, and raising any note by a half step makes it sharp. And, all flat or sharp notes have two names.

Moving up on guitar:

Moving down on guitar:

Moving up on mandolin:

Moving down on mandolin:

Enharmonic Equivalents

“Enharmonic equivalent” is the fancy, music theory way of saying “a note with two names” or “two notes with the exact same sound”. What it means for us is that A# is equal to Bb, G# is equal to Ab, etc.

Here is a list of the most common harmonic equivalents. No need to memorize this, just study the images above and be sure you understand it.

Enharmonic Equivalents:

A# = Bb (A#/Bb refer to the same note on a musical instrument)

C# = Db (C#/Db ” ” “)

D# = Eb (D#/Eb ” ” “)

F# = Gb (F#/Gb ” ” “)

G# = Ab (G#/Ab ” ” “)

And here are some special ones you may never have to see. Since B and C as well as E and F are only a half step apart, when B is raised a half step to B# in music theory the note is the same as C on your musical instrument.

B# = C

Cb = B

E# = F

Fb = E

The Octave

Many of the illustrations we’ve used to this point have begun with an A note and ended with another A note at a higher pitch. The distance between the two A notes is called an octave. The octave interval will become important in the next lesson on Major Scales. We can easily hear that the A of an open string played against the A of the same string 12th fret are very, very similar – they are the same note though one is much higher in pitch. This is because the frequency of the note is doubled at the octave. For instance, if the lower A note frequency is 440 hertz – meaning that a string is vibrating at 440 cycles per second – then the octave occurs when the string vibrates at 880 cycles per second. Each time the frequency doubles, the note has the same name and is said to be raised by an octave. There is no need to memorize this information, just try to understand it. The importance of the octave will be made clear shortly.

Re-cap

In this lesson, we learn . . .

1. Musical distances of a half step, a whole step and an octave.

2. There are twelve notes in Western music.

3. Each next key on piano, and each next fret on a guitar or mandolin represents a half step.

4. Any two notes that skip one key or fret between them are a whole step apart.

5. Lowering any note by a half step makes the note flat; raising any note by a half step makes the note sharp.

6. The natural notes B & C, and E & F are special. There is a half step between B and C and between E and F, and all other natural notes are a whole step apart.

7. Although there are only twelve notes in Western music, many of them share two names.

If you find it difficult to understand any of the concepts in this lesson, take time to re-read the lesson with your instrument of choice at hand, and play the notes discussed in this lesson. Listen to the sounds, and think about how they relate to what is being taught here. You can make suggestions or ask questions by shooting me an email, I’ll do my best to answer.